by Gelya Moreau

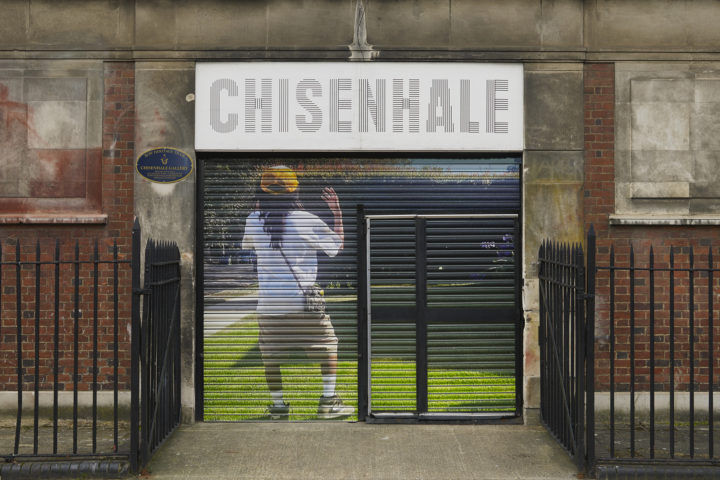

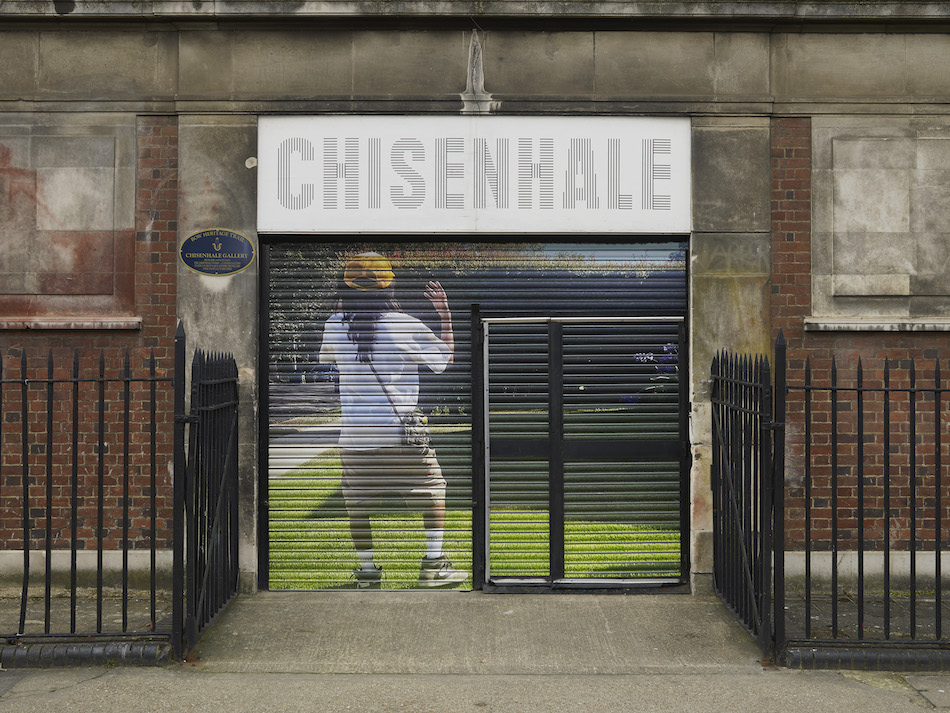

Chisenhale Gallery was founded in the 1980s by artists, and over 40 years later the gallery continues to champion its artist-centred approach giving artists the gift of time and creating an important reverberating effect. Three women lead the East London based institution, Zoé Whitley, the former Director who has recently left the gallery to pursue her career in curating and writing, Charlotte Cole, Deputy Director, and Olivia Aherne, Curator, talked to PROJETS about the gallery and its ambitious programme.

Gelya Moreau

The first thing we learn about Chisenhale is that it is was founded by artists. What role do artists play in the gallery today? Are they still in the heart of its activities?

Zoé Whitley

One of the main ways that we demonstrate that we are artist-centred is by giving artists and the partnerships that we are involved with the gift of time, the time that’s needed to gestate.

We hold in equal balance opportunities for British artists to have an international platform, to be exposed to an international community, and opportunities for international artists to be welcomed into a creative community here in London. Certainly that’s felt urgent since 2020, thinking about Brexit and what our cultural place in the world might be and how we needed to continue to make that as open, fluid, porous as possible and for artists to really feel like they have a home here. I think we do that exceptionally well. Many of the works that we’ve produced go on to be acquired, sometimes immediately, by major collections worldwide.

These reverberations are really important. I often think of our work as reverberative: we are here, in this gallery, in a former veneer factory in East London but the things that happen here, which might initially only be seen by 2,000 people, go on to be seen by 20,000, 200,000 or hundreds of thousands of people. For example, part of Rindon Johnson’s Chisenhale commission was included in the Venice Biennale curated by Adriano Pedrosa. It’s really thrilling to not think only about where this work begins, but also about its many afterlives and where it ends up. I would say, we play a role at a particular pivotal moment in artists’ lives, but they go on to have these other bigger things. It’s wonderful to be a part of that and often to be part of that so early on.

Olivia Aherne

Chisenhale Gallery has a 40-year legacy of commissioning and producing artistic work. It has a history of identifying practices at a particular moment and we use our resources, time, and knowledge of production to support and enrich artistic practices. We produce an artist’s most ambitious work to date, an aspiration that’s different for everyone. We spend up to two years with each artist, transforming an early idea into a final public-facing project – it’s a unique way of working that requires trust, openness and a willingness to experiment.

Two years provides a more generous amount of time compared to many other commissioning opportunities. As so much of that process goes unseen, it feels important to us that each commission is experienced by as many people as possible. Establishing opportunities to partner with peer organisations elsewhere in the world, and for each commission to be seen by as many audiences as possible, is imperative. I like to think of our programme as an incubator for experimental art-making and critical discourse, and an amplifier of the voices of some of the most exciting artists working today.

GM

Reverberating is a really great way to describe Chisenhale. I feel that it’s not only the case for artists, but also for your audience, for all the profound and long-term work that you do with your visitors.

ZW

Absolutely. We are not just making the artwork for ourselves, it’s important that our doors are open and that we’re free to the public. The fact that we are situated in a neighbourhood with a primary school across the street is a really important part of how we see ourselves and what it means to be a public space. I think the main way that we achieved that is through our Social Practice programme. We have an extraordinary curator, Seth Pimlott, who delivers our Social Practice mission to have not only the international reach I talked about, but also to have a community feel, to be a neighbourhood gallery.

There are not many places that aspire to be small and local but what lockdown taught us is that it’s important to be specific, to know who we’re talking to, to engage them and to be that kind of place where we’re never too cool for anybody. We really want to maintain that openness.

If people don’t have the opportunity to come to the gallery, we have to think about how our approach can meet people where they are and still have an impact. So audiences are always that next step in our thinking. We do not want to mediate in the way of being between an artist and an audience, but to facilitate to the greatest degree possible: what does it mean for artists and young people to be able to speak with one another, and for our audiences to really understand an artist’s ideas and approaches because they’re in direct contact with the artist through talks and events?

OA

More often than not, our Commissions result in exhibitions, while our Talks and Events become ways to draw out some of the less obvious or easy to access parts of the research or processes behind each commission. Discursive formats like talks, workshops, performances, and reading groups become ways for us to have more pointed engagements with subjects or methodologies that orbit each commission. All of our programmes are developed in conversation with artists, and they’re moments to gather together with audiences to share ideas and exchange publicly.

ZW

Who do they want to be in conversation with? With the publications that we’ve produced, we’ve been able to facilitate artists having conversations with the leading thinkers that they’ve wanted to be engaged with. For Rachel Jones, that was Claudia Rankine, for Nikita Gayle, that was Hilton Als. A lot of it is about where these connections are possible. To be able to be the conduit for those engagements to happen, that feels like a very important part of what we do. There’s a lot of conversation and dialogue, certainly between the artist and Olivia. I guess we normally summarise it as a kind of critical friendship. It’s about establishing a relationship where there’s that trust there for an artist to hear and know that the person who’s giving the feedback wants the best from the work.

GM

Social Practice led by Seth Pimlott is one of the key pillars of you work here in Chisenhale. This programme has a very beautiful but vague name. What does it actually mean?

CC

There are many names and labels for Social Practice because no organisation has ever been able to reduce it down into a couple of words. It’s about working with people, being part of your community, doing something that gives access to art and expression without rigid boundaries. It could mean working with so many demographics in so many ways, it’s hard to name. We call it Social Practice, and that’s as close as we can come to finding a name that represents the work we do.

Seth Pimlott has transformed it so far beyond what it was before. It has become something so much bigger than one institution. Within Seth’s practice, for example, we work with pupil referral units. These are alternative education provisions where children may have been excluded from their schools for a variety of reasons. And as quite often happens at these moments, children are left with fewer and fewer options, and definitely less and less inspiration. So what can we do, given our responsibility in being part of this neighbourhood? We are a charity in Tower Hamlets, which is one of the poorest boroughs in the UK, with the highest rate of childhood poverty. What can we do to give back, so that we’re not just a gallery with closed doors? Working with pupil referral units, connecting them to artists, art programmes and art practices with them, creating commissions that are about the challenges that they face, this goes some way to opening ourselves to our community.

I think the benefits of multi-year practice are self-evident and critical. Children need consistency. They need repetition in order to feel safe, in order to feel development, in order to feel that maybe the arts are for them. This is not something that comes from a one-off project, which is why Seth and the Chisenhale team strives to build a long lasting programme

GM

How do artists respond to this work?

CC

Artists are at its centre. Chisenhale works with artists for its Social Practice programme whose practice revolves around working with children and young people, or with mental health charities and organisations in the UK.

GM

Zoé, you said that Chisenhale gives the artists the gift of time. Can you tell me more about the way you work with artists? Why do you run by two-year cycles?

ZW

I think because we are a showing space, because we are commissioning and producing new works of art, it takes time. Also because artists need time to not just think about how to deliver something transactionally at the end of it, but to also just meander, to walk down one path and change their mind because they have this new idea.

We do not want them to feel like the clock is ticking so fast and the time is running down so much that they have to pin this down in a month or two months. A lot of it is about allowing what might otherwise be called a creative process to really run its course. It also means allowing some space for mistakes, failure and uncertainty.

OA

While there’s absolutely no expectation that an artist works on their commission solidly for two years, that period of time gives space to be experimental, to change minds, to say actually, that’s not working for me, I’d like to change direction or try something completely different.

Every process is so distinct. When working with an artist whose practice is research-based, a good chunk of the two years might be spent desk-based, researching, or building relationships with other thinkers, writers, and academics whose work can rub up against a project, enriching its conceptual development – often these are long-lasting relationships that go on to sustain practices far beyond the commissions themselves.

Other times we might be working with an artist that has a studio practice and the emphasis is on experimental making or setting them up in a studio here in London so that they can work site-responsively. Other times it’s about exploring something totally new.

GM

Chisenhale is know for its ambitious programme. How do you identify the artists that you would like to work with?

ZW

: It’s as complicated and as simple as seeing a lot of art. You have to be engaged in the world around you. You see art and you talk to artists is how that works. Olivia and I are invited on a regular basis to do crits at various art colleges in London, but it’s also important that we spend time in the rest of the UK to be aware of what’s happening outside of London, and certainly in Europe.

We can’t always expect things to orbit around us or come to us. We go out and ask questions.

We really are an artist’s art gallery: the core of our audience base are other artists. So we are the gallery where artists come to see artworks. In many cases artists that we’ve worked with in the past, introduce us to the practices of artists that they’re teaching or somebody that they’re excited about.

There are lots of different ways, there’s no one formula, but you just have to see a lot of work in order to know what’s exciting, what makes sense, how might we be able to help support an artist in that next step. We really want to be part of that process of thinking what might we be able to offer that would help an artist do something that they haven’t been able to do before.

OA

Identifying artists that are pushing the boundaries of art-making and critical thinking, but haven’t yet had an opportunity to make work at this scale, drives our decision making. It’s really important that our programme is diverse, supporting different ways of making, different forms of discourse, as well as artists working in different geographical contexts including the UK.

GM

Do you build long-term relationships with artists after their exhibition is over? Do you continue to engage with the artists? Are they involved in any way in what you do?

OA

Developing new work of increased ambition, and over the course of two years, requires a level of trust and vulnerability, so these relationships are often long-lasting. When works that we commission and produce go on to be presented elsewhere, we tend to be the touchpoint for restaging or stewarding those works – it’s always incredibly exciting when we get to return to earlier commissions, to understand the way they resonate today. Artists that we work with, more often than not, reference previous commissions as influential reference points – it’s always a joy to bring new artistic voices into contact with those that we’ve worked with before.

In addition, many Chisenhale artists go on to support us as trustees too. There’s a huge amount of continued engagement, friendship and support, which is reciprocal as we continue to champion and advocate for those that trust us with their work and shape who we are.

GM

It feels like commissioning in collaboration with other institutions and partners is key to the way Chisenhale functions.

ZW

It is part of that reverberative effect. We put so much effort and energy into realising a commission. You want as many people to see it as possible. It goes back to your previous question about audiences. We want people to engage with the work. And so if you’re working with like-minded peer organisations, then that only amplifies the opportunities for the work to be seen. Equally, because so much work has been put into it, it’s important to share resources. That feels like a necessary part of how we want to approach things. I also think it has a lot to do with using resources responsibly. I think we’ve moved away from an institutional model where you have to be a solitary figure to be seen to be important or taken seriously. Being stronger together or teaming up is an important thing to think about.

OA

One of the very early conversations we have with artists is about where their work hasn’t been shown and where/how they would like to develop visibility. This often triggers a conversation about which other institutional contexts their commission might be shown in after its London premiere, and what additional support and input that might unlock in order to bring ambitious and bold artistic ideas to fruition. We’re in constant conversation with peers and other organisations to understand programme alignments as partnerships really give our commissions the amplification we believe they deserve.